You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

OT: Politics & News... Have at it.

- Thread starter lapin

- Start date

XPOFAN

New member

Conservative MP Eve Adams crosses floor

http://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/conservative-mp-eve-adams-crosses-floor-1.2227221

http://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/conservative-mp-eve-adams-crosses-floor-1.2227221

lapin

Active member

Obama is full of shit. Do some real homework on how the unemployment rate is calculated.

Bingo, Ringo !

lecoqsportif

Well-known member

Obama is full of shit. Do some real homework on how the unemployment rate is calculated.

Except those tweets are about employment levels, not the unemployment rate. So, no, they are not wrong. Still doesn't address the participation rate issue.

BTW, the wage growth issue is a bigger deal. That really is better news.

northernlou

Idi Admin

Lou is right, we've seen an unprecedented uncoupling of the unemployment rate and the participation rate in the United States.

But "transparency"? The Part-rate has always been published publicly (http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS11300000). But the U-rate is the headline rate for the media, always has been. I'm not sure it the Administration's fault much of the media and civil society is illiterate in economics.

Anyway, good job raising the Part-rate, I've been banging on about this for quite some time.

You'll have to excuse my late response. I've had a lot less time to myself lately.

To your post now, which I'll reproduce as we go along.

That's right we agree on the part-rate. That's nice. However, the fact that the part rate is published on a .gov website, doesn't do enough to counter all the charges by the MSM, across the board, about this admin's lack of transparency, nor does it put to rest any of the many well documented falsehoods this admin has put out there.

But, hey, now that we're introducing new indicators to assess the economic wellbeing of American households, why not introduce a few more:

Economic mobility: http://www.frbsf.org/economic-resea...r/2013/march/us-economic-mobility-dream-data/

Income inequality: http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3629

Wealth Inequality, from The Fookin' Man: http://www.amazon.ca/Capital-Twenty-First-Century-Thomas-Piketty/dp/067443000X

I cannot overstate the importance of Piketty's work, and not that "political action" (e.g. tax policy, labour law, etc.) is very much a valid solution. Oh, and in the name of transparency, he put all the data on line publicly to allow other people to test out his theory: http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/fr/capitalisback

Now, you see Lou, these are all losing issues for the GOP and get far closer to the source of economic insecurity of American households than the Part-rate, which is just a symptomatic measure. But no one wants to talk about that, because that's "class warfare".

Regarding Piketty's work. He's tried to assemble aggregate tax data from centuries past to make his point. Yet solid economists as I'm sure you're aware, have questioned his results and how he got there. He may well be the beginning, or a starting point, but how you can see him as the last word on income inequality. Larry Summers, while praising Piketty's work, also points out doesn't take capital depreciation into account when valuing capital. If so this throws 'r' off. Others have pointed out basic errors in historical facts. What I'm stressing is, there's enough reason...not to disparage Piketty's work....but not to take it as the last word.

Anyhow, income inequality won't matter a shit if the US doesn't get it's fiscal house in better order.

Anyway, back to the Great Recession and the part rate. Yep. Something should more have been done. But what? Well, the Fed did all it could do with QE. Short-term interest rates were basically zero, so they had no traction. Bernanke did what he could, despite Mensa-Club-Chart-Member Rick Perry's bizarre/crazy threats (http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/aug/16/rick-perry-ben-bernanke-treasonous), buying up $3.8 trillion of long term instruments and pumping that money into the financial system to unplug credit markets.

But, the part rate, right? Still down. And GDP is still well below potential despite this unprecedented infusion by the Fed. So, the zero lower bound for interest rates is clearly a hinderance to an effective response, the Fed can only do so much with QE. What to do. What to do. Hmmmm.

Well, when stuck at the ZLB, one proper response is:

http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/072113.pdf

And what did the Obama Administration do?

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/43945-ARRA.pdf

So... they kinda did the "right thing".

But this adds to the debt, right? Oh no! Evil debt! You've railed consistently about deficits/debt, right? But what about the poor little unemployed people? Think of the children, do something! But interest rates are already zero, tax rates on upper incomes are already low thanks to the Bush income and capital tax cuts, and tax cuts to lower income households will just be funnelled to under-water mortgage repayment... so there's no wiggle room there.

Fiscal. F@cking. Stimulus. That's why so many think the stimulus was far to small, and improperly structured (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/artic...-more-fiscal-stimulus-needed-in-u-s-tom-keene). So, Lou, where was the f@cking GOP on the stimulus? Eh? Evil debt! Exploding inflation!* And now, in 2015, many years after the scene of the crime, screaming about debts/deficit, idiotic threats to default on the debt, ... and now you're f@cking worried about about labour market outcomes?

So, let me make this clear: your arguments about the Administration's economic policies are completely incoherent. They are a contradiction at the most basic level. So, by all means, stress out pointlessly about the deficit (it's mostly irrelevant). Or worry, far more usefully, about the unemployed. But you cannot do both in a ZLB, because it is total bullshit.

* Can't wait to see your conspiracies about the inflation rate. I'll bring the tin foil.

That's right the Fed's done it all with the QE and (as well as self serving to justify more debt and hold down the cost of borrowing) near zero interest rates. But aren't these prog backed Keynesian styled policies anyway? And despite all this, and not to mention the stimulus, the GDP under-performs? This must mean something is failing here. Do I have to be an economist to see this?

Now maybe if the stimulus was more pro growth oriented, things could have been brighter, but that's not where it went. Obama today incessantly whines about $$$ for roads and bridges, which admittedly could improve commerce, but wait, that's what he promised when he sold his ARA to the public. He sold oodles of new green jobs and a new economy. The dishonesty of this stimulus is right there in it's implementation and how it differed in structure with the TARP bailout. TARP being a one time cash infusion that was repaid...the near $trillion ARA, was added to the US budget from here to eternity, where in the future it can be spent on other priorities. Which in all likelihood will be devoted to the huge growth in entitlement spending.

And 6 years later a preponderance of McJobs lead the way in Obama's new economic recovery. That's the reality. And you call for more spending and scoff at growing national debt.

Progs as well as yourself like to tell us that the sky is the limit with spending. Even prog icon Krugman tells us today that we don't understand debt, how it differs from traditional debt that we borrow from others, while national debt is money we borrow from ourselves.

Well that's quite a change in tune from just a short decade ago.

If there's any reason to doubt the counter intuitive argument offered by Dems regarding limitless debt. It's in their own hypocrisy and huge flip flop on the issue. And this includes icon Krugman.

The Dems went absolute berserk over Bush's spending, which is far smaller than Obama's contribution to this. Obama himself called Bush's bloating debt as irresponsible and unpatriotic. Pelosi and the rest of the gang and the MSM pounded the point home consistently.

and now for two faced, ideologue Krugman. The icon who tells us debt is no prob today, how most us just don't understand. I ask when did he get epiphany on this, perhaps after Obama was elected. In fact about the only criticism you get from Krugman on Obama, is that the stimulus wasn't big enough. When in fact, it could have been better spent and structured differently by allocating for project that could lead to more economic activity.

Krugman:

Krugman, in a November 2004 interview, criticized the "enormous" Bush deficit. "We have a world-class budget deficit," he said, "not just as in absolute terms, of course — it's the biggest budget deficit in the history of the world — but it's a budget deficit that, as a share of GDP, is right up there."

The numbers? The deficit in fiscal year 2004 — $413 billion, 3.5 percent of the gross domestic product.

Back then, a disapproving Krugman called the deficit "comparable to the worst we've ever seen in this country. ... The only time postwar that the United States has had anything like these deficits is the middle Reagan years, and that was with unemployment close to 10 percent." Take away the Social Security surplus spent by the government, he said, and "we're running at a deficit of more than 6 percent of GDP, and that is unprecedented."

He considered the Bush tax cuts irresponsible and a major contributor — along with two wars — to the deficit. But he also warned of the growing cost of autopilot entitlements: "We have the huge bulge in the population that starts to collect benefits. ... If there isn't a clear path towards fiscal sanity well before (the next decade), then I think the financial markets are going to say, 'Well, gee, where is this going?'"

Three months earlier, Krugman said, "Here we are more than 2 1/2 years after the official end of the recession, and we're still well below, of course, pre-Bush employment." In October 2004, unemployment was 5.5 percent and continued to slowly decline. At the time, Krugman described the economy as "weak," with "job creation ... essentially nonexistent."

How bad will it get? If we don't get our "financial house in order," he said, "I think we're looking for a collapse of confidence some time in the not-too-distant future."

Fast-forward to 2010.

The numbers: projected deficit for fiscal year 2010 — over $1.5 trillion, more than 10 percent of GDP.

This sets a post-WWII record in both absolute numbers and as a percentage of GDP. And if the Obama administration's optimistic projections of the economic growth fall short, things will get much worse. So what does Krugman say now?

We must guard against "deficit hysteria." In "Fiscal Scare Tactics," his recent column, Krugman writes: "These days it's hard to pick up a newspaper or turn on a news program without encountering stern warnings about the federal budget deficit.

The deficit threatens economic recovery, we're told; it puts American economic stability at risk; it will undermine our influence in the world. These claims generally aren't stated as opinions, as views held by some analysts but disputed by others. Instead, they're reported as if they were facts, plain and simple."

He continues, "And fear-mongering on the deficit may end up doing as much harm as the fear-mongering on weapons of mass destruction." Krugman believes Bush lied us into the Iraq War. Just as people unreasonably feared Saddam Hussein, they now have an unwarranted fear of today's deficit.

http://www.creators.com/opinion/larry-elder/krugman-bush-s-deficit-bad-obama-s-deficit-good.html

and more on the ever evolving wisdom of Krugman, as I continue my then vs now exposure of utter Dem hypocrisy and outright lying to the American people on this subject....and among others actually.

New York Times columnist Paul Krugman doesn't see any problem with the huge deficits being run up by President Obama. In a column released to national newspapers in October, he claimed that Obama's deficits are coming down dramatically and nobody on the "right wing" is praising the president for that.

First of all, the deficits aren't really coming down that much. According to the Office of Management and Budget, the deficit only came down by about $30 billion (4.5 percent) in the most recent fiscal year. (To see the budget deficit data, go to www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historicals.)

This is a far cry from the Krugman of the George W. Bush years, when he said that Bush's deficits — which were ALL lower than in any Obama year — would cause a "fiscal train wreck." In 2003, Krugman said that he was "terrified about what will happen to interest rates once financial markets wake up to the implications of skyrocketing budget deficits. . . . We're looking at a fiscal crisis that will drive interest rates sky high."

In 2010, when Obama was running up the second of his four trillion-dollar-per-year deficits, Krugman wrote: "These days it's hard to pick up a newspaper or turn on a news program without encountering stern warnings about the federal budget deficit. The deficit threatens economic recovery, we're told; it puts American economic stability at risk; it undermines our influence in the world. These claims generally aren't stated as opinions, as views held by some analysts but disputed by others. Instead, they're reported as if they were facts, plain and simple. Yet they aren't facts." He also defended one of his favorite presidents by saying "The long-run budget outlook is problematic, but short-term deficits aren't — and even the long-term outlook is much less frightening than the public is being led to believe."

Which is true — Krugman's 2003 concerns over small deficits or his 2010 acceptance of larger deficits?

Here are the uncomfortable facts about each president, taken from the White House's own website:

Total deficits in eight years under Bush: $2.005 trillion (average $250 billion per year)

Total deficits in six years under Obama: $6.422 trillion (average $1.07 trillion per year)

The "iron law of modern liberalism," espoused most eloquently by Krugman, seems to be that budget deficits are dangerous under Republicans but necessary under Democrats. They hurt the nation when they are $412 billion under Republicans, but they help the nation when they rise to more than $1.2 trillion under a Democrat. If this isn't cynical partisan propaganda, then what would you call it?

http://www.moneynews.com/MikeFuljenz/Krugman-deficit-budget-Obama/2014/11/03/id/604776/

And this is just a small sample of what's out there on the net. Anyone wishing to find more on how DEMS viewed debt just 10 short years ago, and isn't just in it for themselves can hunt it down on their own instead of listening to the double talk.

Now Obama on debt as lying candidate.

[video=youtube;DyLmru6no4U]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DyLmru6no4U[/video]

the steam can't rise off the bullshit fast enough.

And more from people a lot smarter than me I presume on the consequences of runaway debt. Not my musings lecoq that you find so condescendingly funny. From the good people at the left of center Brookings Institute.

* As detailed in publications of the Congressional Budget Office, a Brooking Institution paper authored by Alan J. Auerbach (University of California, Berkeley) & William G. Gale (Brookings Institution), and a Princeton University Press book authored by Carmen M. Reinhart (University of Maryland) & Kenneth S. Rogoff (Harvard University),[121] the following are some potential consequences of unchecked government debt:

• reduced "future national income and living standards"[122] [123] [124];

• "reductions in spending" on "government programs"[125];

• "higher marginal tax rates"[126];

• "higher inflation" that increases "the size of future budget deficits" and decreases the "the purchasing power" of citizens' savings and income"[127] [128];

• restricted "ability of policymakers to use fiscal policy to respond to unexpected challenges, such as economic downturns or international crises"[129];

• "losses for mutual funds, pension funds, insurance companies, banks, and other holders of federal debt"[130]; and

• increased "probability of a fiscal crisis in which investors would lose confidence in the government’s ability to manage its budget, and the government would be forced to pay much more to borrow money."[131] [132]

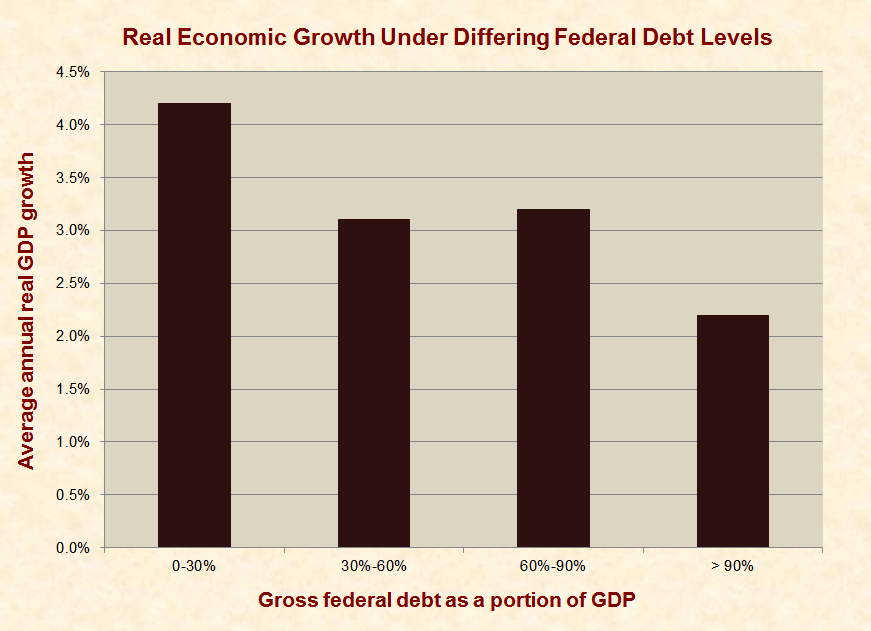

* In 2012, the Journal of Economic Perspectives published a paper by Carmen M. Reinhart (University of Maryland), Kenneth S. Rogoff (Harvard University), and Vincent R. Reinhart (chief U.S. economist at Morgan Stanley). Using 2000+ data points on national debt and economic growth in 20 advanced economies (such as the United States, France, and Japan) from 1800-2009, the authors found that countries with national debts above 90% of GDP averaged 34% less real annual economic growth than when their debts were below 90% of GDP.[133]

* The United States exceeded a debt/GDP level of 90% in the second quarter of 2010.[134]

* Per the textbook Microeconomics for Today:

* In 2013, the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, published a working paper by Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash, and Robert Pollin. Using data on national debt and economic growth in 20 advanced economies from 1946-2009, the authors found that countries with national debts over 90% of GDP averaged 31% less real annual economic growth than when their debts were 60-90% of GDP, 29% less growth than when their debts were 30-60% of GDP, and 48% less growth than countries when their debts were 0-30% of GDP.[136]

* The authors of the above-cited papers have engaged in a heated dispute about the results of their respective papers and the effects of government debt on economic growth. Facts about these issues can be found in the Just Facts Daily article, "Do large national debts harm economies?"

http://www.justfacts.com/nationaldebt.asp

Anyhow, this is a terribly long winded post and I don't like the time they take. But I just have stress the importance of not buying in to what you're selling, while still recognizing that some well pointed gov't stimulus can be of value if it can in fact improve economic growth while still respecting the limitations and pitfalls of poorly thought out spending and debt.

so as you can see, my conspiracy theories that you think you need a tin foil hat for, are shared by very learned people from the best of institutions, many of which are center left thinkers, including Icon Krugman & the lying Dem party, just one presidency ago.

Last edited:

Louis, do you worry more about yank politics than Canadian politics?

northernlou

Idi Admin

I've always found their politics and history much more captivating and consequential than our own.

lecoqsportif

Well-known member

@ Lou

1. The assertion that the Fed is "holding down" interest rates for the benefit of borrowing is nonsense and seems a little paranoid. The Fed has a dual mandate: price stability and full employment. If the Fed had maintained positive short-term rate and had not engaged in QE we would be in big, big trouble (see Europe - the Germans have been the poster boys of policy incompetence). Indeed, smart conservative economists (like Scott Sumner, who I very much respect even if I'm not totally convinced by his arguments) have consistently argued the recession was cause by a monetary policy that was too tight prior to 2008 and were absolutely on board with Bernanke's approach.

2. The "McJobs' issue is absolutely a problem, but the forces behind that are structural (most due to technology, poor education outcomes) and not cyclical. This is a decades-long productivity challenge that start long before Bush or Obama and will go on well beyond them. This is more of a Piketty issue.

3. I also strongly dislike the accusation of people being labeled "unpatriotic" because of policy disagreements. That goes for everyone. I find it stupid. (Same with people being called "Hitler". It's ridiculous.)

4. Your critique of Krugman off base. Maybe with a political lens he seems to be a hypocrite, but from an economic lens it's not the case. Based on prevailing economic conditions, which is what should drive policy decisions, the Bush tax cut made no sense (and very few economic benefits). All those bad things caused by debt are very much in play when you are not zero bound constrained and utilizations rates are pretty much at capacity. That was, I can assure, nowhere near the case after 2008 - there were few private sector resources to displace, businesses and households were in a full blown balance sheet correction. Here's the thing: fiscal policy should only be deployed in one case: the zero lower bound. It would have been ineffective in the previous recessions, the right response is monetary (the hero in the early 80s wasn't St. Raygun, it was Paul Volcker). But in the post-2008 environment, due to the ZLB and a huge balance sheet melt down, fiscal policy was very much a valid tool (as noted by those wild-eyed pinkos as the IMF). In terms of root causes and consequences, 2008 wasn't the father's recession... it was the grandfather's depression.

5. The Reinhardt and Rogoff work was, very publicly, debunked due to calculation mistake (as was the 90% threshold). It was embarrassing.

6. Yes, there are some consequences to borrowing, even minor ones in a ZLB. But there are costs with all choices, including doing nothing. Policy choice aren't made in a vacuum, they are made on a cost-benefit basis. And sometimes the short-term pain is not the right option. I would rather be the QE/tepid fiscal policy US than tight money/Europe right now and in the future.

7. I don't "believe" in unlimited spending. I think aggressive fiscal measures are warranted when the circumstances dictate. I was opposed to the stimulus in Canada, and as I noted above, I think it was basically pointless in the early 80s. The US has massive economic capacity to carry more debt, and they have the economic scenario that called for additional deficit financing. I have consistently argued that pre-2020 they need to stabilize the economy, and post-2020 they need to stabilize the public accounts.

8. You still have't addressed the core issue that you can't complain about both deficit and unemployment in the zlb. Post-2008 was a singular environment, you can't compare it to the 2002-2003 period.

1. The assertion that the Fed is "holding down" interest rates for the benefit of borrowing is nonsense and seems a little paranoid. The Fed has a dual mandate: price stability and full employment. If the Fed had maintained positive short-term rate and had not engaged in QE we would be in big, big trouble (see Europe - the Germans have been the poster boys of policy incompetence). Indeed, smart conservative economists (like Scott Sumner, who I very much respect even if I'm not totally convinced by his arguments) have consistently argued the recession was cause by a monetary policy that was too tight prior to 2008 and were absolutely on board with Bernanke's approach.

2. The "McJobs' issue is absolutely a problem, but the forces behind that are structural (most due to technology, poor education outcomes) and not cyclical. This is a decades-long productivity challenge that start long before Bush or Obama and will go on well beyond them. This is more of a Piketty issue.

3. I also strongly dislike the accusation of people being labeled "unpatriotic" because of policy disagreements. That goes for everyone. I find it stupid. (Same with people being called "Hitler". It's ridiculous.)

4. Your critique of Krugman off base. Maybe with a political lens he seems to be a hypocrite, but from an economic lens it's not the case. Based on prevailing economic conditions, which is what should drive policy decisions, the Bush tax cut made no sense (and very few economic benefits). All those bad things caused by debt are very much in play when you are not zero bound constrained and utilizations rates are pretty much at capacity. That was, I can assure, nowhere near the case after 2008 - there were few private sector resources to displace, businesses and households were in a full blown balance sheet correction. Here's the thing: fiscal policy should only be deployed in one case: the zero lower bound. It would have been ineffective in the previous recessions, the right response is monetary (the hero in the early 80s wasn't St. Raygun, it was Paul Volcker). But in the post-2008 environment, due to the ZLB and a huge balance sheet melt down, fiscal policy was very much a valid tool (as noted by those wild-eyed pinkos as the IMF). In terms of root causes and consequences, 2008 wasn't the father's recession... it was the grandfather's depression.

5. The Reinhardt and Rogoff work was, very publicly, debunked due to calculation mistake (as was the 90% threshold). It was embarrassing.

6. Yes, there are some consequences to borrowing, even minor ones in a ZLB. But there are costs with all choices, including doing nothing. Policy choice aren't made in a vacuum, they are made on a cost-benefit basis. And sometimes the short-term pain is not the right option. I would rather be the QE/tepid fiscal policy US than tight money/Europe right now and in the future.

7. I don't "believe" in unlimited spending. I think aggressive fiscal measures are warranted when the circumstances dictate. I was opposed to the stimulus in Canada, and as I noted above, I think it was basically pointless in the early 80s. The US has massive economic capacity to carry more debt, and they have the economic scenario that called for additional deficit financing. I have consistently argued that pre-2020 they need to stabilize the economy, and post-2020 they need to stabilize the public accounts.

8. You still have't addressed the core issue that you can't complain about both deficit and unemployment in the zlb. Post-2008 was a singular environment, you can't compare it to the 2002-2003 period.

Last edited:

lecoqsportif

Well-known member

I've always found their politics and history much more captivating and consequential than our own.

For sure.

wiseguy1

Well-known member

I've always found their politics and history much more captivating and consequential than our own.

Do you think the University of Toronto has an opening for a professor of American History and Politics?

northernlou

Idi Admin

@ Lou

1. The assertion that the Fed is "holding down" interest rates for the benefit of borrowing is nonsense and seems a little paranoid. The Fed has a dual mandate: price stability and full employment. If the Fed had maintained positive short-term rate and had not engaged in QE we would be in big, big trouble (see Europe - the Germans have been the poster boys of policy incompetence). Indeed, smart conservative economists (like Scott Sumner, who I very much respect even if I'm not totally convinced by his arguments) have consistently argued the recession was cause by a monetary policy that was too tight prior to 2008 and were absolutely on board with Bernanke's approach.

2. The "McJobs' issue is absolutely a problem, but the forces behind that are structural (most due to technology, poor education outcomes) and not cyclical. This is a decades-long productivity challenge that start long before Bush or Obama and will go on well beyond them. This is more of a Piketty issue.

3. I also strongly dislike the accusation of people being labeled "unpatriotic" because of policy disagreements. That goes for everyone. I find it stupid. (Same with people being called "Hitler". It's ridiculous.)

4. Your critique of Krugman off base. Maybe with a political lens he seems to be a hypocrite, but from an economic lens it's not the case. Based on prevailing economic conditions, which is what should drive policy decisions, the Bush tax cut made no sense (and very few economic benefits). All those bad things caused by debt are very much in play when you are not zero bound constrained and utilizations rates are pretty much at capacity. That was, I can assure, nowhere near the case after 2008 - there were few private sector resources to displace, businesses and households were in a full blown balance sheet correction. Here's the thing: fiscal policy should only be deployed in one case: the zero lower bound. It would have been ineffective in the previous recessions, the right response is monetary (the hero in the early 80s wasn't St. Raygun, it was Paul Volcker). But in the post-2008 environment, due to the ZLB and a huge balance sheet melt down, fiscal policy was very much a valid tool (as noted by those wild-eyed pinkos as the IMF). In terms of root causes and consequences, 2008 wasn't the father's recession... it was the grandfather's depression.

5. The Reinhardt and Rogoff work was, very publicly, debunked due to calculation mistake (as was the 90% threshold). It was embarrassing.

6. Yes, there are some consequences to borrowing, even minor ones in a ZLB. But there are costs with all choices, including doing nothing. Policy choice aren't made in a vacuum, they are made on a cost-benefit basis. And sometimes the short-term pain is not the right option. I would rather be the QE/tepid fiscal policy US than tight money/Europe right now and in the future.

7. I don't "believe" in unlimited spending. I think aggressive fiscal measures are warranted when the circumstances dictate. I was opposed to the stimulus in Canada, and as I noted above, I think it was basically pointless in the early 80s. The US has massive economic capacity to carry more debt, and they have the economic scenario that called for additional deficit financing. I have consistently argued that pre-2020 they need to stabilize the economy, and post-2020 they need to stabilize the public accounts.

8. You still have't addressed the core issue that you can't complain about both deficit and unemployment in the zlb. Post-2008 was a singular environment, you can't compare it to the 2002-2003 period.

1. The Gov't benefits from near zero interest rates for borrowing purposes no doubt about that. And Keynesian spenders have been calling for more borrowing given the favorable conditions, this is no secret and certainly not kind of paranoid.

2. Agreed the McJobs issue has more history than just Obama, but he did promise lots of good paying jobs in his new economy, green jobs, infrastructure projects and that sorta thing. I don't recall much about a boon in fast food and cafe careers.

3. Fine, we both don't like the "you're not a patriot" thing. However, the larger point of that vid showing Obama saying those things about Bush's (at that point) unprecedented debt build up. It is the fact that Obama was railing against runaway Gov't spending and mortgaging their future to China's loan masters. He was going to cure all that crazy.

4. I stand by my Krugman comments. Smaller debt by Bush bad. Much larger debt by Obama, no problemo. Debt is debt, lecoq.

5. I'll answer this in a subsequent post, shortly, soon after the rest of your points.

6. On this we agree in part. On the fiscal side I'm much more....conservative.

7. I call it unlimited spending because I don't know what the Keynesian spending ceiling might be. Does anyone?

8. This isn't a core issue. Mine is with spending. I brought up the US labor participation rate to put the new lower unemployment rate, that some people think is great.....into perspective and to further support my earlier post from Gallup, (The Big Lie: 5.6% Unemployment) that delved into what is a deceptive employment rate, based on how it is calculated. And of course, as is fact, most of the new jobs are just McJobs. All this came up just a couple pages back.

No, not everybody knows this. And this is not about Obama changing the formula....just spreading the lie that has an economy producing more low paying, low hour McJobs than anything else.

And this business of unemployment in the zlb, hold on....perhaps critics can do that, since lots of jobs and a steady decrease in unemployment were promised by Obama while selling the ARA back in 09'.

Last edited:

northernlou

Idi Admin

@ Lou

5. The Reinhardt and Rogoff work was, very publicly, debunked due to calculation mistake (as was the 90% threshold). It was embarrassing.

The Reinhardt and Rogoff study, of course, the one I cited claiming that economic growth is ridiculous by high debt thresholds, particularly above 90% of gdp. You said it was discredited, and it was, well...sort of.

However, Reinhardt and Rogoff did later admit to that and corrected what was a coding error.

The criticism or discrediting of the RR study was due to the work of Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash, and Robert Pollin of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts....aka HAP.

Anyhow, R&R responded with another study in 2013 known as RR&R now. In it they did admit to error which they corrected. Now the eye opening thing about this RRR paper, it reached similar conclusions to the HAP work that discredited their 90% threshold in the first place.

The following is an article that was linked after the RR citation from the justfacts website I had referred to. I'll let it explain the rest.

***********************************************************

Do large national debts harm economies?

Advocates for higher government spending are abuzz over a new working paper that disputes a famous paper often trumpeted by conservatives. The famous paper found that high levels of national debt are associated with lower economic growth, a result that conservatives have repeatedly cited to argue that governments should stop accumulating debt.

This new working paper exposes calculation errors in the famous paper, critiques its methodology, and presents competing findings. Liberals have latched onto these findings to argue that nations should be less concerned with government debt and should increase government spending to “stimulate” their economies.

While the authors of the working paper make significant contributions to this debate, they and numerous commentators who are citing their work have used their findings to mislead rather than inform. They have done this by leveling false accusations, ignoring an important follow-up paper written by the same authors, and failing to reveal that the new findings are similar to that of the famous paper: high levels of national debt are associated with slower economic growth.

Primary Findings

For a 2010 paper published in the American Economic Review, Carmen M. Reinhart of the University of Maryland and Kenneth S. Rogoff of Harvard University researched and tabulated the national debt and economic growth in 20 advanced economies (such as the United States, France, and Japan). Using 2,000+ data points from over 200 years, the authors found that “high debt/GDP levels (90 percent and above) are associated with notably lower growth outcomes.” Relevantly, U.S. federal debt surpassed 90% of GDP in 2010 and has now reached 105% of GDP.

However, Reinhart and Rogoff’s paper has come under withering criticism in a working paper written by Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash, and Robert Pollin of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Herndon, Ash, and Pollin [HAP] assert that the Reinhart and Rogoff [RR] paper suffers from “coding errors, selective exclusion of available data, and unconventional weighting of summary statistics,” which “lead to serious errors that inaccurately represent the relationship between public debt and GDP growth….”

The existence of at least one coding error is a reality that RR admit is “a significant mistake in one of our figures….” Furthermore, this coding error appears to pervade the entire paper, a point that RR have yet to formally acknowledge. Beyond this, the other issues raised by HAP boil down to subjective interpretations of how data should be averaged and the use of data that was not verified until after RR’s paper was published.

Most importantly, even if one uncritically accepts all of HAP’s methods, their primary results are basically similar to RR’s: countries with debt/GDP ratios higher than 90% have notably lower economic growth. HAP’s results are graphed here:

Misrepresenting the Results

Despite the association between debt and economic growth found by HAP, reporters and commentators have been leading their audiences to believe no such relationship exists. For example, Ben White and Tarini Parti of Politico reported that RR’s paper underwent a “very public demolition” at the hands of HAP, who found that economic growth “in countries with debt over 90 percent of GDP was around 2.2 percent, not much different from lower debt countries.”

In fact, HAP found that advanced countries with national debts over 90% of GDP had 31% less economic growth than when their debts were 60-90% of GDP, 29% less growth than when their debts were 30-60% of GDP, and 48% less growth than when their debts were 0-30% of GDP. As explained further below, these are significant differences with important implications, and Politico is not alone in masking these realities.

The Washington Post‘s editorial board wrote that HAP’s paper “debunks” RR’s “famous 2010 finding that a national debt-to-gross domestic product ratio above 90 percent may substantially moron economic growth.” A headline in the American Prospect has declared that “Reinhart and Rogoff’s Theory of Government Debt is Dead,” and Mike Konczal of the Roosevelt Institute has claimed that “one of the core empirical points providing the intellectual foundation for the global move to austerity in the early 2010s was based on someone accidentally not updating a row formula in Excel.” Countless other individuals and organizations have made similar claims.

These misrepresentations are somewhat understandable given the manner in which HAP present their findings. Their abstract denies any association between debt and economic growth, claiming that “average GDP growth at public debt/GDP ratios over 90 percent is not dramatically different than when debt/GDP ratios are lower.” What do they mean by “dramatically different?” One has to read ten pages into HAP’s paper before they provide a side-by-side comparison of the figures they arrived at for economic growth under different levels of debt: “The actual growth gap between the highest and next highest debt/GDP categories is 1.0 percentage point (i.e., 3.2 percent less 2.2 percent).”

To those unfamiliar with this issue, “1.0 percentage point” may not sound like much, but in this context, it amounts to 31% less economic growth per year. Compounded over time, this can cause genuine harm to people. For example, if economic growth in the U.S. were reduced by 1.0 percentage point per year over the past 20 years, GDP would have been $13.1 trillion in 2012 instead of the $15.7 trillion that it was. This portends far-reaching negative consequences, such as more poverty and reduced life expectancy. As explained in the textbook Microeconomics for Today:

"GDP per capita provides a general index of a country’s standard of living. Countries with low GDP per capita and slow growth in GDP per capita are less able to satisfy basic needs for food, shelter, clothing, education, and health."

In a recent New York Times op-ed, Pollin and Ash (two thirds of HAP) write that a “coding error and partial exclusion of data” by RR altered one of their results for economic growth by 0.6 percentage points. They perceptively note that this difference “is quite substantial when we’re talking about national economic growth.” Yet, in their paper, HAP characterize a much larger 1.0 percentage point difference in national economic growth as “not dramatically different.”

Cause and Effect

One of the most important critiques of RR and those who have favorably cited their research concerns the issue of causality. In basic terms, HAP and company argue that slow economic growth causes high debt and not vice-versa. In the words of Mark Gongloff of the Huffington Post, RR “imply strongly that high debt causes slow growth, when there is no evidence for that.”

In truth, there is prominent evidence for this, but HAP and many others have ignored it. In 2012, the Journal of Economic Perspectives published a paper by RR and Reinhart’s husband, Vincent R. Reinhart, the chief U.S. economist at Morgan Stanley. In this paper, these scholars (hereafter referred to as RRR) specifically addressed the issue of cause and effect. Yet, from reading HAP’s paper and many news reports and commentaries about this issue, one would never even know that this paper existed.

RRR took a straightforward approach to the matter of cause and effect by limiting their analysis to “prolonged periods of exceptionally high public debt, defined as episodes where public debt to GDP exceeded 90 percent for at least five years.” They found that these countries averaged 1.2 percentage points or 34% less economic growth than when debt was below 90% of GDP. Note that this figure is very close to the 31% difference found by HAP. RRR explain the significance of this with regard to cause and effect:

Following Reinhart and Rogoff (2010), we select stretches where gross public debt exceeds 90 percent of nominal GDP on a sustained basis. Such public debt overhang episodes are associated with lower growth than during other periods. Even more striking, among the 26 episodes we identify, 20 lasted more than a decade. The long duration belies the view that the correlation is caused mainly by debt buildups during business cycle recessions.

RRR emphasize that the cause-and-effect issue has not been “definitively addressed,” but they assert that “the balance of the existing evidence” from their study and other recent studies “certainly suggests that public debt above a certain threshold leads to a rate of economic growth that is perhaps 1 percentage point slower per year.” This is precisely the figure arrived at by HAP.

This does not mean that cause and effect can’t run in both directions. No one disputes that economic recessions can increase government debt, and constructive debate over this matter will surely be ongoing. Nonetheless, there is a clear association between high debt and slow growth, and substantial evidence that the former can cause the latter.

continued....

Summary

Condensing the key points above, there is a clear relationship between high levels of debt and slow economic growth. This is a not a universal rule but a robust association based upon extensive observations and disparate mathematical methods. The precise strength of this relationship is debatable, but existing results center around the outcome that growth in countries with debt over 90% of GDP is about 30% lower than when debt is below this level. There is also considerable but not definitive evidence that high debt can cause slow growth, as well as vice versa.

The current U.S. debt is at 105% of GDP and is projected to keep growing under current polices. This elevated level of debt may be a factor in weak economic growth that the U.S. has been experiencing, but advocates for increased government spending are blaming this and other problems on reduced government spending. This is in spite of the fact that since 2008, government spending has been much higher than it has been for the vast majority of U.S. history.

Last edited:

northernlou

Idi Admin

Pretty interesting read with moucho accreditation that strongly, in not definitively suggesting lower growth when coupled with high debt in and around 90% of GDP.

Pretty interesting read with moucho accreditation that strongly, in not definitively suggesting lower growth when coupled with high debt in and around 90% of GDP.

In the end , the final result is the same .... Corporate America and the elite made all the money from

QE and every other benefit that was given since the they were the only ones who had the means to participate .

The middle class got wiped out and has gained nothing in the last 10 years. Main stream USA GOT SMOKED

Suspect in Denmark Terror Attacks killed:

http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/15/europe/denmark-shooting/index.html

A quote from the Danish prime minister:

""This is not a battle between Islam and the West, and it is not a battle between Muslims and non-Muslims, but a battle between the values of freedom for the individual and a dark ideology.""

Actually it's clearly a war on an evil cult vs the democratic values of everyone else, let's stop sugar coating what this really is.

http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/15/europe/denmark-shooting/index.html

A quote from the Danish prime minister:

""This is not a battle between Islam and the West, and it is not a battle between Muslims and non-Muslims, but a battle between the values of freedom for the individual and a dark ideology.""

Actually it's clearly a war on an evil cult vs the democratic values of everyone else, let's stop sugar coating what this really is.

21 Coptic Christians killed in the name of Allah by ISIS:

http://www.cjad.com/cjad-news/2015/02/15/video-purports-to-show-21-isis-beheadings-in-libya

http://www.cjad.com/cjad-news/2015/02/15/video-purports-to-show-21-isis-beheadings-in-libya

northernlou

Idi Admin

"random"